The past two years have been especially brutal to so-called equity ‘bears’. Against all odds, and despite all the shocks, global capital markets—if not the real economy they are supposed to represent—have continued to climb to new heights. After the onset of the coronavirus catastrophe, the relentless rise of the asset markets, particularly in the U.S., has completely baffled many.

But it should not. We are in the midst of an asset market mania—perhaps the biggest of all time.

All the while we have been warning about the possibility of collapse of the world economy, beginning in March 2017, when we issued our first-ever warning of global crash. Then we wrote:

The crisis of 2007 – 2008 reversed the trend of financial globalization, which has undermined global growth. The pull-back in financial globalization has been masked by central bank-induced liquidity and continuous stimulus from governments which have created an artificial recovery and pushed different asset valuations to unsustainable levels. This implies that we live in a “central bankers’ bubble”.

We have noted in several times this year how central banks and especially the Federal Reserve (or the “Fed”) has been acting as the ‘de facto’ market-loss back-stopper, successfully pushing asset markets to new heights. However, it is obvious that the central bankers are only following the script they had written before. This is no ‘New Normal’.

So, let’s take a tour of the bailouts over the past 11 years.

Starting with a bang

In the depths of the Global Financial Crisis at the end of 2008, standard monetary policy tools became ineffective. After slashing the Fed funds rate below one percent in October 2008, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided that more drastic action was needed.

Fed officials came up with the idea (not a new one, actually) to start buying assets from the secondary market. Probably to make such a measure sound like a sophisticated component of an up-to-date arsenal of monetary policy, it was called quantitative easing, or “QE”.

The Fed, when beginning the current cycle of QE-programs (the Bank of Japan ran a similar program from March 2001 till March 2006; more on that later), linked QE tightly to the ability of a central bank to lower short-term interest rates to the ‘zero lower bound’, where short-term rates are zero (the Fed has less control over longer-term rates, though it can affect them, too.)

During the first round of QE, enacted on November 25, 2008, the Fed bought marketable securities issued by U.S. Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSE) and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). In March 2009, the program was extended to include purchases of U.S. Treasury debt.

China to the rescue

When the financial crash of 2008 resulted in a burgeoning global recession, Chinese leaders enacted USD multi-trillion infrastructure programs that powered the world economy out of a deep ditch into a renewed upward trajectory. These programs were financed by credit issued by state-controlled banks, which Beijing can essentially compel to lend. As Beijing ordered banks to ramp-up lending, the banks responded by doubling the volume of loans on a year-over-year basis—a truly fantastic level of stimulus.

Between 2007 and 2015, 63% of all new money created globally came from China, and most of this increase was created by Chinese commercial banks. Such colossal credit stimulus pushed the world economy, and especially Europe, into a fast recovery, and without it, the story after the GFC would almost certainly have been completely different.

And the bailouts kept on coming…

But the Chinese were not the only players on the field. To get a sense of the consistency and extent of these coordinated interventions, let us review the main bailout operations of the past ten years:

- In October 2010, the Bank of Japan started to buy Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) linked to the Japanese stock market. It became customary that the BoJ would begin to buy whenever the Topix stock market index fell more than a 0.2 percentage points by midday.

- In August 2012, the European Central Bank enacted the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program to halt the rise in sovereign yields in the Eurozone.

- In 2015, the Chinese economy started to roll over again. Authorities directed funds for investment through the shadow banking sector which led to an unprecedented credit spree.

- Also in 2015, in an effort to devalue the Swiss Franc, the Swiss National Bank started to “invest” in foreign assets, including U.S. equities including many of the top technology names. In many cases, such purchases by the SNB coincided with episodes of increased market turbulence, as during the first rate-hike cycle of the Fed in 2016-2017.

- During 2017 central banks across the globe forced over $2 trillion worth of artificial central bank liquidity into the global markets, mostly through their aggressive asset purchase programs.

- In December 2018, the People’s Bank of China started to support the domestic banking sector by injecting hundreds of U.S. billions worth of liquidity into the system to stop a run on the weaker banks in the system.

The ‘pivot’ of the Fed

On January 4, 2019, following a three-month long market rout which escalated in early January, the Fed pivoted from its firm assurances of several interest rate rises in 2019 and automated balance sheet run-off that would be like “watching paint dry.”

Between January and March 2019, the Federal Reserve made a complete U-turn. In early December 2018, Chairman Powell was still anticipating several interest rate rises for 2019, but by March they had reverted to possible cuts and ending the balance sheet normalization program altogether.

The Fed cut interest rates for the second time for the year in August 2019, and the ECB pushed rates further into negative territory and restarted its QE-program in September. The majority of central banks globally dutifully followed suit.

Despite these desperate efforts, the repurchase agreement (“repo”) markets blew up in September 2019, forcing the Fed to intervene in this market for the first time since 2009. This was also the likely starting point for a resumption of the ongoing global financial crisis.

And then the coronavirus pandemic struck.

In comes the Corona shock

On March 16th, 2020, rates on the U.S. short-term bonds, on which cities and states often rely for their short-term financing needs, exploded higher. Liquidity and buyers evaporated from several key parts of the U.S. capital markets, including corporate fixed-income and even Treasury markets.

There was an immediate sense of panic in the stock markets. On the March 16th, 2020, the “implied volatility index” or “VIX”, of the U.S. stock markets reached 82.69, the highest on record, ever. The DJIA plunged by 2,997 points, or 12.9 percent, the worst point drop on record. And then, the authorities stepped in.

On the 16th, the New York Fed announced that it would add $500 billion in overnight loans to the repo-market. On Tuesday, the 17th, the Fed announced that it would use $1 trillion to mop-up corporate paper from issuers. On Wednesday, the 18th, the ECB announced that it would buy 750 billion euros worth of bonds and securities. On the 19th, the Fed announced that it would create a lending facility to support money-market mutual funds. Other central banks across the global launched similar support operations.

And now, we are here.

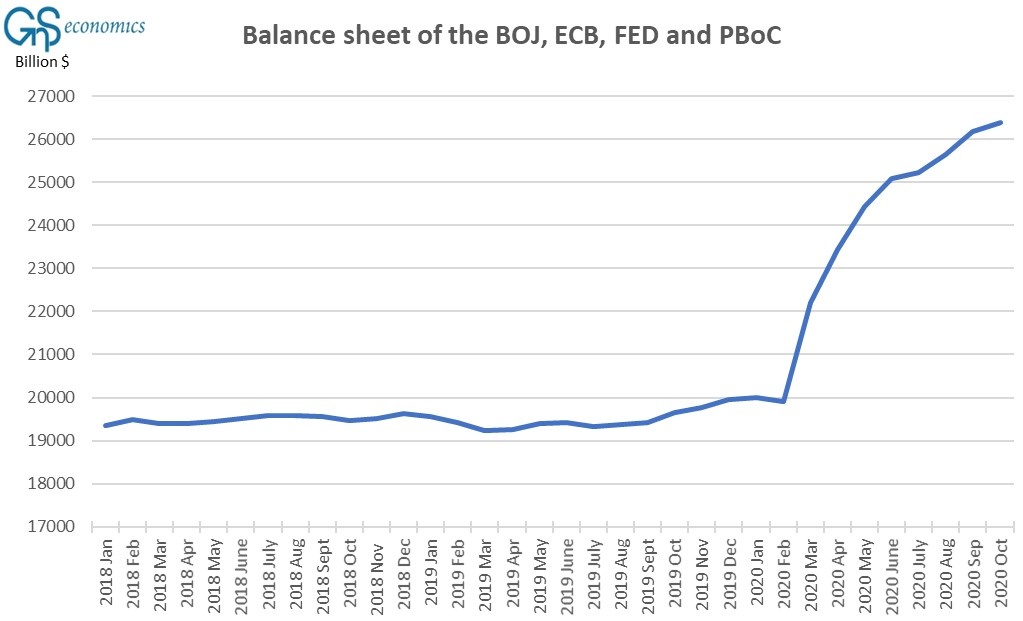

Figure. The combined balance sheet of the BoJ, ECB, Fed and PBoC. Source: GnS Economics, BoJ, ECB, Fed, PBoC

Is this the ‘New Normal’? (No)

Many seem to be under the impression that this sort of thing can go on forever. In all fairness, judging from the past, their case seems to be supported by facts. If central banks have been able to keep everything from falling apart up to this point, why couldn’t they simply keep on going indefinitely?

We outlined the ways central banks can fail—or become obsolete—in Q-Review 3/2019. Effectively, it always requires a political decision to either audit or dismantle a central bank, or to not recapitalize in the case of overwhelming capital loss. However, there is an additional ‘neutron bomb’ to consider, a factor the central banks cannot control: the banking system.

If confidence between large financial institutions in the all-important “interbank market” is broken, there is practically nothing a central bank can do to fix it. It can provide cheap loans to banks, but they are just loans.

If, for example, there is a risk of sudden re-emergence of foreign exchange risk, and a redenomination of outstanding loans in that currency, banks will reprice this risk in the interbank markets, which may then freeze-up. This is a real risk in the Eurozone with the possibility of various national “exits”, and the likely reason why the ECB is pushing so hard for the acceptance of the “recovery fund”. We have detailed the specifics of this kind of financial crisis in this blog.

So, there are, in fact, several ways central banks can lose control of the today’s highly-levered and highly-speculative financial systems. And, when that happens, look out below!

More information

December issue of our Q-Review will deal with the Aftermath -scenarios of the coronavirus pandemic. Check out our year-end offer for Annual Q-Review Subscriptions from GnS Store

Stay informed how the world economy and the global economic crisis through our Q-Review reports and Deprcon Service, which are available at GnS Store