For some reason, the dire situation of European banks is not causing alarm. This is strange, as it is the exact place where the new global banking crisis is likely to start.

What makes it even stranger is that recession is approaching the Eurozone, and the “zombified” European banking sector is unlikely to be able to cope with it. Because of its vast size (banking sector assets are some 240% of the GDP of the Eurozone), the European banking crisis will spread. This is why everyone should be worried.

How did the European banking sector arrive at this sorry pass? It’s the end of a long road of continuous and worsening policy failures.

Sowing the seeds of trouble

The response of the European authorities to the financial crash of 2008 was notably different from that of the US. While around 165 banks failed in the U.S. in 2008 and 2009, only a few banks failed in Europe, and those were mostly concentrated in one country, Iceland, where the whole banking sector collapsed.

In total 114 banks received government support in Europe during the crisis. The recovery of the European banking sector from the crisis was notably slow. However, this should not have come as a surprise. Europe had failed to heed the lessons of Japan. If ailing banks are not wound down or re-capitalized properly, they will linger in the economy as “zombies” slowly poisoning the economy.

Banks were also allowed to carry non-performing loans and assets on their balance sheet. This meant that:

- Banks held defaulted loans on their balance sheets, instead of writing them off.

- Assets, like mortgage-backed CDOs, that had lost most or all of their value could be held on the balance sheet based on their “nominal value”, that is, at their purchase price.

Thus, effectively, the European banking sector transitioned from ‘mark-to-market’, where the value of their assets was based on actual daily market quotes, to “mark-to-fantasy”, where banks could arbitrarily determine the value of their assets. This helped to create zombie banks all over Europe.

OMT: From bad to worse

Mario Draghi’s ‘Outright Monetary Transactions’ (“OMT”) program eased the burden of the banks by pushing yields of government bonds across the Eurozone down (bond prices up). But this also helped to support ailing banks, which then engaged in “zombie lending” meaning that they provided credit to infirm or even insolvent borrowers.

Moreover, corporations that received these loans did not use them to increase capital expenditures or to hire workers, but rather to build cash reserves. Creditworthy firms suffered greatly from this misallocation of credit further hurting the Eurozone economy. So, while the OMT program was perceived as the saviour of the Eurozone, it also doomed the Eurozone to stagnation–and worse was yet to come.

The desolation of negative rates (and QE)

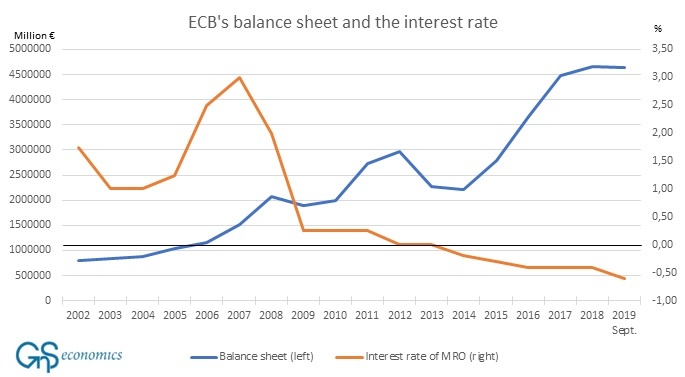

In accordance with the “pioneering” macroeconomic academic view at the time, the ECB pushed interest rates to negative in June 2014. This posed a major problem for banks, as most of their profits arise from the interest rate differential between lending and borrowing (taking deposits). This difference essentially determines a bank’s profitability.

When a central bank pushes rates negative, banks are usually still obliged to pay interest on customer deposits, who tend to be reluctant to pay interest on money they place at a bank. Thus, low interest rates narrow the difference between lending and borrowing rates, which vanishes or inverts completely with negative interest rates.

Squeezed profit margins lead to falling profitability of banks and to diminished lending activity. Negative rates thus actually ended up being a drag on the economy of the Eurozone.

Yet, the suffering of the European banking sector did not end there.

Following the footsteps of Ben Bernanke’s Federal Reserve, the ECB launched its own quantitative easing program in March 2015. In it, it bought both sovereign and corporate debt.

As we detailed in a post past year, QE altered the net interest margins, the liquidity portfolio and the duration of the assets of commercial banks. This induced the banks to increase lending and to move their portfolio towards riskier lending activities. QE also pushed interest rates on sovereign bonds to unnatural lows making them look less-risky than they actually were. Thus, QE increased the financial fragility of the banking system in Europe.

In essence, negative interest rates and the OMT and QE -programs were a ‘triple whammy’ for the European banking sector.

The ticking time-bomb

The problems of the European banking sector were mishandled from the 2008 crisis on. Almost every decision European authorities took made the situation of banks worse. In addition to grave monetary policy mistakes, the regulatory framework was also tightened, which pushed bank profits even lower.

As a result of all these policy mistakes, a large part of the European banking sector has probably been insolvent for the past 10 years, a conclusion that is also suggested by the group’s stock price performance for that same period. The sector simply never recovered from the 2008 crisis.

How will the ‘living dead’ European banks cope with the recession that is approaching fast? The only plausible answer is: not well. They are a ticking time-bomb.

Global reach and preparation

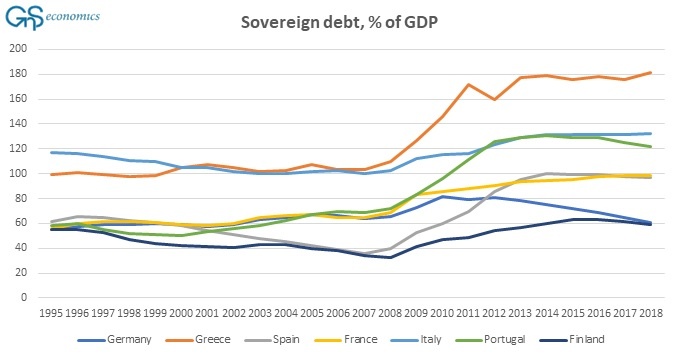

The fatal policy mistakes of the ECB and Europe’s incomplete and insufficiently-funded banking union mean that the handling of the crisis will again fall on the sovereign states, which are considerably more indebted than in 2008 (see Figure 2). This also guarantees that banks will actually fail this time around, unless bailed-in by depositor funds (i.e. consumer deposits at the banks).

Because of the vast size and global reach of European banks, the crisis will go world-wide in an instant. This means that the “flames” of the banking crisis of Europe will spread and bring in their wake a global depression.

Due to the global asset market bubble, hiding places for investors will be few and far between. Moreover, when the crisis hits, exits from the over-valued capital markets are going to be very, very small. Preparation is the key!

Buy the Crisis Preparation II: The Eurozone-report detailing how and where to seek for asset safety in Europe fromGnS Store

Buy the Q-Review 2/2019: Prepper’s Bunker -report, where we present how to preserve liquidity heading into the crisis and how to benefit from the coming crisis, fromGnS Store

Annual subscription of our Q-Review reports, with access to all older reports, is available atGnS Store